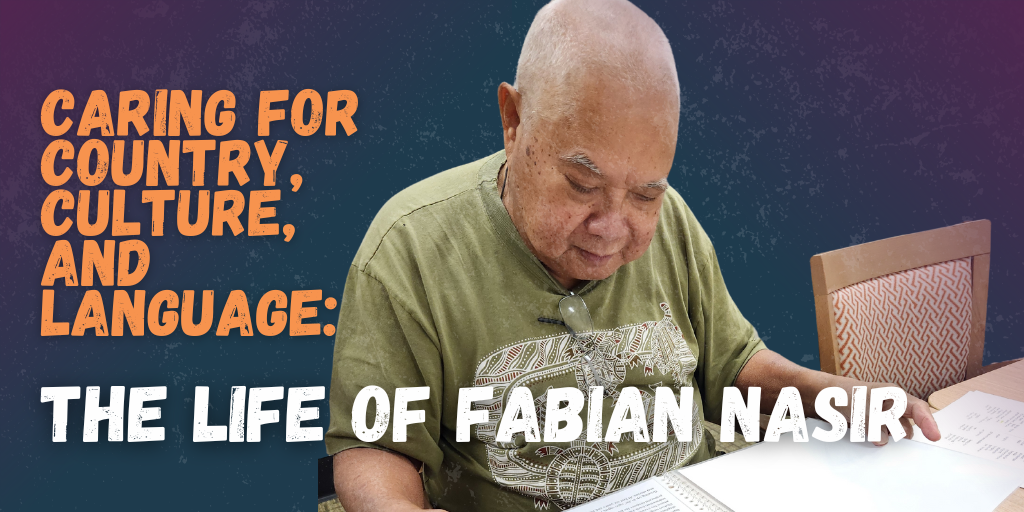

Caring for Country, Culture, and Language: The Life of Fabian Nasir

Readers please be advised this article mentions people who have passed away. Photos in this article, and this story was shared with permission from Fabian Nasir.

At 82 years old, Hassan Fabian Bin Nasir from the Minyirr Djukun Clan stands as a living testament to resilience, cultural pride, and the enduring spirit of the Djukun Nation. As the oldest living Djukun descendant, Fabian is at the forefront of a remarkable mission to revive the Djukun language—a sleeping language that he is determined to awaken. His dedication to this cause is as personal as it is cultural, rooted in a lifetime of experiences that have shaped his commitment to preserving his heritage.

Born in Port Hedland, during World War II, Fabian’s early life was marked by displacement as his family was evacuated from Jirr’ ngin-ngan-Broome in the Djukun language. They returned after the war, bringing Fabian back to his roots, where his connection to the land and his culture deepened. His father, an Indonesian hard-hat diver, and his mother, a Djukun woman, instilled in him a profound respect for both his cultural heritage and the land of Jirr’ ngin-ngan.

Growing up in Jirr’ ngin-ngan, Fabian’s childhood was rich with traditional practices and stories. At just six years old, he learned to play the piano, taught by Mother Raymond, a nun at the Jirr’ ngin-ngan convent. These lessons, held in the nun’s living quarters after school, left a lasting impression on him. Though his piano lessons ceased when he relocated to Darwin, Fabian has never forgotten the tunes he learned, such as Beethoven’s “Für Elise,” which he can still play today.

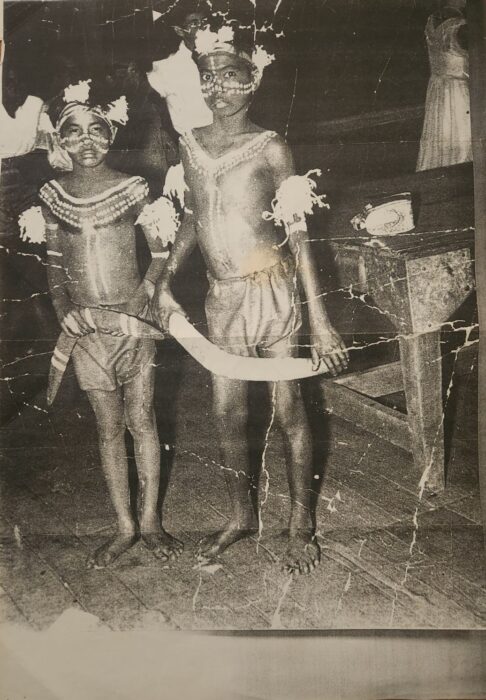

Fabian also fondly recalls hunting Nimmanburroo-Flying Fox in the Djukun language-and fishing with his uncles, were everyday activities that grounded him in his cultural identity. Fabian vividly remembers the significance of certain signs, such as the presence of a snake indicating an abundance of fish. He remembers collecting seasonal bush foods, walking the shores of Jirr’ ngin-ngan in search of octopus, and checking the family-owned fish trap with his brothers. He recalls participating in cultural practices, where he was painted up and mangrove wood shavings were used as adornments, he felt deeply connected to his people and culture, leaving an indelible mark on him. These experiences not only enriched his childhood but also fuelled his passion for preserving his cultural heritage.

This photo has been in Fabian’s family, taken in Broome 1950’s. Fabian Nasir (R) & Brother James Nasir (L)

Fabian’s life journey took him from Jirr’ ngin-ngan to Darwin, where he pursued a career as an electrician, heeding his father’s advice to avoid pearl diving. His work brought him face-to-face with the devastation of Cyclone Tracy in 1974, where he played a vital role as an essential worker in helping Darwin and outlying communities rebuild by repairing fallen powerlines and installing power generation. This work was a testament to his resilience and dedication, even as he faced significant challenges.

Throughout his life, Fabian encountered racism, which began in primary school where he was called Aboriginal instead of by his name. The constant taunts continued through to adulthood, where he was told, “You don’t look Australian,” to which he would always reply, “Well, what does an Australian look like?” and was denied payment for his electrical work because of the colour of his skin. Despite these trials, he found moments of significance, such as ensuring the power supply for Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s historic visit to Wattie Creek in 1975, where Whitlam poured the soil into the hands of Gurindji Leader Mr Lingiari, marking a pivotal moment in Australian history.

Fabian, a staunch advocate for caring for Djukun Country, holds deep respect for his ancestral homelands. He emphasises the importance of “fishing for the future and teaching the younger generation the way.” Fabian fully supports the recent petition to protect Billingooroo, a place filled with cherished memories for him.

Expressing his concerns, Fabian states, “Australia says fair go. How about giving Billingooroo a fair go? Respect the country, respect the traditional custodians of the land, respect the rocks, and leave them where they are.” Fabian’s words serve as a powerful reminder that respecting Indigenous rights and the environment is a responsibility we all share.

Now retired, Fabian remains a vibrant force in the Djukun community, dedicating his time to the Djukun language revitalisation project. His efforts to awaken the Djukun language are deeply personal, as he draws on the wisdom and knowledge acquired through his rich life experiences. As he peruses the Daisy Bates Djukun word list for the first time, his eyes light up. Fabian points to the words he remembers from his childhood. Familiar words like Womba (Man) and Ngai (l, Me). These memories, tied to hearing some of the last fluent Djukun speakers on Djukun Country, fuel his passion for reconnecting younger generations with their roots and instilling pride through their language and culture.

Fabian’s dedication is encapsulated in his words: “We have to revive our Djukun language; it’s who we are. Gala yangarda (let’s go), Djukun Nation.” His vision for the future of the Djukun language is clear and urgent, driven by a love for his heritage and a commitment to ensuring it’s survival.

Fabian Nasir’s journey is one of hope and resilience for the Djukun Nation. His life story, marked by cultural immersion, professional challenges, and historic moments, serves as an inspiration for all who are involved in the preservation and revitalisation of Indigenous languages. Through Fabian’s efforts, the sleeping language of Djukun is stirring and ready to be spoken once more by future generations. His legacy will be one of cultural revival, ensuring that the Djukun language and traditions are not only remembered but also celebrated and lived.

Author Jaala Ozies with Fabian Nasir

Author Jaala Ozies with Fabian Nasir

This article was originally published on Djukun Nation.