Appropriate terminology for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – it’s complicated.

I run a media, training and consultancy company called IndigenousX. It is 100% Indigenous owned and staffed. We work on local, regional, national, and international projects; we run training workshops on anti-racism, digital strategies, and media training. We run school incursion programs on Indigenous science.

We get to do some really amazing and important work but wherever we go, regardless of the scope of work, some non-Indigenous person will invariably ask something along the lines of “What is the most appropriate term to refer to Indigenous people in Australia?”

I get asked about it so often that it is usually our first interactive session when we do our anti-racism workshops and our communications workshops.

People who ask this question are usually hoping for a checklist of dos and don’ts, or better yet a one or two word answer but the best I can do in that short a word count is ‘It’s complicated”.

(Before I go on to explain this further, I’d like to acknowledge that whenever an Indigenous person writes an article on a topic like this someone invariably writes a reply article complaining that there are more important topics to write about, and they’re not wrong. And while it may not be as important as writing an article about how there are more important articles to write about, without ever actually going on to write about those other important topics, I think if we can get a few more people to stop asking this question it’ll be a real timesaver for me and for other Indigenous people who constantly get asked this question, and maybe it’ll even generate better understanding for some people as well, so I’m going to do it anyway… also, someone asked me to write this for a different outlet but then couldn’t use it so I figured I might as well put it here).

Whenever I get asked this question I always picture that opening scene of the classic 1986 Australian mockumentary, BabaKiueria.

It opens with white people enjoying a weekend down at a local park (barbecuing, drinking, littering, playing cricket etc), when out of nowhere a group of Indigenous soldiers, armed with rifles, appear in a boat approaching the shore.

A crowd gathers, they come on land and plant an Aboriginal flag.

I hereby claim Twitter on behalf of @IndigenousX…. all your tweets are belong to us. pic.twitter.com/bVD7Wb8GwA

— Pearson In The Wind (@LukeLPearson) January 7, 2016

Their leader approaches a man in the crowd and, in that slow clear voice that is so helpful for communicating with people who don’t speak your language, asks “What… do you… call… this place?”

The man, clearly confused by what is happening, answers, “Its… it’s a barbecue area”.

He replies, “BabaKiueria?” he turns back to his men, “They call this place BabaKieuria.” Then he says, mostly to himself as he takes a look around, “Nice, native name. Colourful. I like it!”

*Cue title card and music*

It is not a one-to-one parallel though, because in naming what we call Australia ‘BabaKiueria’ he did something that white invaders to this land did not – he took what he (albeit wrongly) believed to be their name for the continent.

In the actual version, it was more like “We don’t care what you call this place, it’s now called ‘Australia’. Oh, and here’s some smallpox for your troubles.”

Iit is important to point out here that most peoples have a name that is derived from place – Spanish people are from Spain and English people are from England (and from America, Australian, New Zealand, South Africa, but I might be jumping the gun if not the shark there, so we will come back to this point).

Aboriginal people, however, do not come from Aboriginalia.

We were not given a name derived from place, and our own names for ourselves and for our places were largely ignored.

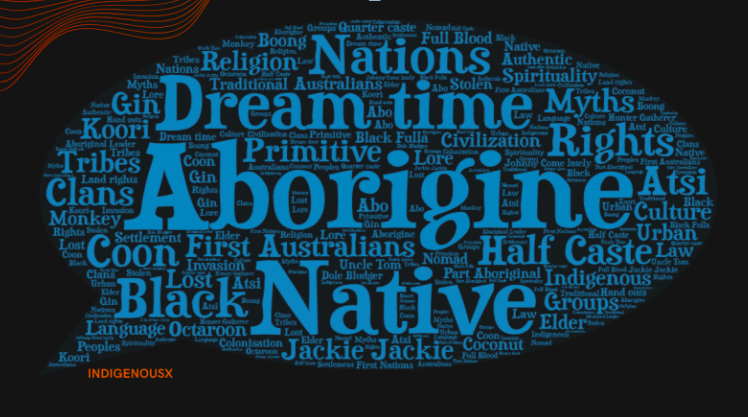

We were given not a name as such, but rather a classification, ‘aboriginal’, ‘natives’, ‘indigenous’, much in the same way as flora and fauna are.

It always amazes me to think there was a very real chance in those early days that Aboriginal people today could well be known as Cookians, in much the same way as people were once called ‘Rhodesians’ after super racist Cecil Rhodes, or how Torres Strait Islander people today are named after some guy named Torres who I am guessing… sailed a boat near them once?

It’s also worth noting that lots of people we think have a name derived from place have a name derived from the name white people gave the place rather than their actual names – colonisation is nothing if not convoluted, and really racist… mostly racist.

We couldn’t have had a single collective name for all the Indigenous peoples who occupy the continent and surrounding islands which white people decided to call ‘Australia’ as no language group ever had such a term, let alone a term that we all could have shared across languages.

We had no pan-Indigenous identity that would necessitate such a name in the first place.

It is in this context that the search for ‘appropriate terminology’ only exists for two distinct reasons. Firstly, as a convenience for non-Indigenous people so they don’t need to learn about all the different nation groups that exist, and for Indigenous peoples ourselves to unite behind a common struggle.

As for the latter, because I do not care about the former, different groups over time began to organise and to advocate on such terms and in doing so shifted from terms of classification (natives, aborigines, indigenes, blacks etc) to proper nouns and proper adjectives, that is to say, people started to demand their capital letters the same as everyone else had.

They took their classifications and made them names – proper nouns and proper adjectives.

The power in doing this is not insignificant. Its purpose was to takes us from a thing to be labelled, an object to be studied, to a group of people with agency and with rights.

Different names took off to different degrees of success in different areas, with some people rejecting any such labels in favour of their own original names.

There are no more powerful examples of this than when Rosalie Kunoth-Monks appeared on Q&A and declared “ I am not an Aboriginal or, indeed, Indigenous. I am Arrernte, Alyawarre, First Nations person, a sovereign person from this country”.

And, as language does, these capitalised terms have changed and adapted over time:

Native has dropped out of use, capitalised or not.

Blood quotient and percentage based terminology has largely been rejected, much like the eugenics based policies that spawned it.

Aborigines has largely disappeared in favour of Aboriginal people/s (except for a few older people who haven’t kept up with the times and a few racist commentators trying to make the point that *checks notes* they are cartoonishly racist).

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people/s has hung around but not without conflict – having to maintain itself against government attempts to shorthand it to ‘ATSI,’ first in writing and then vocally, upon which point a lot of people pushed back enough that it is no longer acceptable usage within government agencies or institutions.

Indigenous people/s became popular in the 1990s, introduced by some Indigenous academics as an attempt to align with global Indigenous communities in time for the first Year of the World’s Indigenous peoples in 1993. A lot of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples didn’t like this though because they felt it was being pushed by government forces who were indeed early adopters of the term, I suspect grateful for an opportunity to move from 45 characters (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples) to 18 characters (Indigenous peoples) without being criticised in the way they were over the whole ATSI debacle.

Black/black/Blak/Blackfullas Commonly used by mob but generally avoided by white institutions and media, which is probably a good thing.

First Nations has become popular in recent years, a term borrowed from North America, and one which I myself am slowly becoming more comfortable with on the basis that if that’s what the next generation want to do then who am I to get in their way?

First Australians can be found in various government style guides but if I was to go out on a limb I would imagine that was because they saw First Nations gaining popularity and when someone brought it up in their annual style guide meeting they were shut down because to use that term would challenge the perceived sovereignty of Australia, and so a ‘compromise’ term was put forward instead – First Australians. Personally, I am not a fan of this one myself we are actually the last people who were allowed to have citizenship status which would make us more accurately the Last Australians.

There are other terms too, and a lot of these will stay or go depending on how the next generation of Indigenous people see them, in part this will be influenced by how badly white people try to ruin them for everyone, which is a big part of the reason why Aborigine faded away, and why I worry about any of the ones that start with ‘First’:

🥸😱😂😭 https://t.co/ZIjgbvj3lL pic.twitter.com/LniI86DUdu

— Pearson In The Wind (@LukeLPearson) April 30, 2021

There are further complications to these terms too, like if you want to add ‘Australian’ on the end of them. I am much more comfortable being referred to as an Aboriginal person than I am as an Aboriginal Australian. Much like the Government Style Guide team, my hesitation has to do with the validity of Australia’s alleged legitimacy as a sovereign nation.

And on everything I have discussed it is further complicated by the nature of collective Indigenous consensus making which currently has no support for any form of mechanism to bring elevated representatives together to discuss and debate such matters. As such, these conversations play out thousands of times online and in real life as people discuss, debate and share their own preferences and their reasons for them.

As for individual preferences, lots of Indigenous people have their own preferences shaped by their upbringing, their philosophy, their community, and countless other factors so saying ‘but I know someone who…’ is a poor excuse for most things in life, but especially when arguing against a different individual who is asking you as an individual not to call them something they don’t like to be called.

It’s not for me as an individual to say… each term has its advocates and detractors, so it’s more about understanding each one and then making your own informed choice so if anyone asks ‘but why do you use this terminology?’ you have a better answer than ‘because Luke said’.

— Pearson In The Wind (@LukeLPearson) June 14, 2021

This is trickier for corporations who can’t hope to tailor their language to suit individual preferences so what becomes important for them is to be able to say they have shown some effort to engage with Indigenous staff and community within their organisation and taken thought in choosing whatever terminology they decide to go with. I might not always like the answer they end up with but of they can demonstrate an appropriate and respectful process then I have to respect that.

Similarly though, white people have no consensus on how they should be called, or whether or not white should be capitalised. They also rarely have to consider this point though because of the nature of settler-colonialism. They simply get to take a name derived from place, even if that place is not theirs, hence so many white people who don’t feel a need to have an adjective qualifying their Australianness, or any other qualifying characteristics of their race or their status, they get to just be ‘Australian’. Nobody asks them ‘but where do you really come from?’ or tells them to go back to where they came from, or tries to force them to assimilate to the laws of the land, unless doing so ironically to make a point akin to the one I am making now.

It is for everyone else to reflect on the labels white people give us and fight to assert our own identities outside of the boxes they try to put us in – ethnic, indigenous, multicultural, diverse, migrant, etc.

It is for everyone else to fight for our terminologies, for our capital letters, for our right to belong unchallenged and unquestioned, for our right to determine for ourselves even something as simple as our own names.