Do monuments hold any value?

In consideration of Invasion (Australia) Day in 2021, debate will again turn to a need to produce and recognise a more open and critical story of colonial violence. While some in the wider community will again campaign to shift the date of national celebration away from a day that commemorates invasion – January 26 – to a more inclusive date, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people will continue to campaign for Australia Day to be abolished completely.

An associated narrative that has gained traction, both in Australia and internationally in recent years, inspired in part by the Black Lives Matter movement, has been the debate around monuments, specifically statues that celebrate the lives of ‘great white men’ often responsible for crimes of violence against Indigenous and enslaved peoples. In addition to campaigning for the removal of celebratory monuments, some which have already been toppled or defaced by activists, Aboriginal people in Australia have also demanded that the murder and massacre of our people be publicly commemorated.

I have reflected on and written about these issues for many years now. In general, I agree with the need to decommission and remove any monument that uncritically celebrates empirical conquest and violence. The presence of such statues is not only deeply offensive to Aboriginal communities. They inhibit the potential for truth-telling and the ability to produce the more honest and mature story that this country desperately needs.

2020 marked the 250th year since James Cook set foot on Aboriginal land. There had been plans for a replica of Cook’s boat, the Endeavor, to visit Australia last year. Covid 19 put an end to the regal tour before a sail was set. Cook, a contested figure in colonial history, is commemorated ad nauseum across the nation. Statues of Cook have been periodically defaced. While calls for their removal have been vocal, they tend to fall on ears of selective colonial deafness. The defacement of colonial monuments, being clear acts of provocation, are effective, in that they interrogate the fragile foundations of colonial history and expose the naked emperor.

On this basis it is worth hypothesising that if we retain some colonial monuments in the knowledge that the story they privilege will continue to be contested by Aboriginal writers, artists and activists, such actions may provide opportunities for necessary debates about our past. Early in December last year I was in Cairns and stumbled across the infamous eight-metre-high statue of James Cook, which has stood sentry in the city, on Sheridan Street, for fifty years. Cook salutes the heavy road traffic passing by. Some have described the salute as ‘Nazi-like’. Consequently, Cook offends on several levels and thousands of signatories have petitioned for the statue’s removal.

The Cook statue also suffers from Australia’s fixation with gigantism. Most of us are familiar with giant bananas, pineapples, lobsters, puppy dogs and my favourite, the Giant Koala at Dadswell’s Bridge in western Victoria, which allows visitors to the Koala to (disturbingly) disappear into its bowels. The Captain Cook of Cairns is particularly odd-looking. As well as being extremely tall, he is unhealthily thin, the skinny man of the Empire, who could be easily be mistaken for John Cleese performing Basil Fawlty in period dress. A large sign alongside the statue not only advertises the pleasures of the nearby ‘Cock & Bull Pokies’, but also ‘FOOD’ in very large font, perhaps mocking this Cook’s lack of girth.

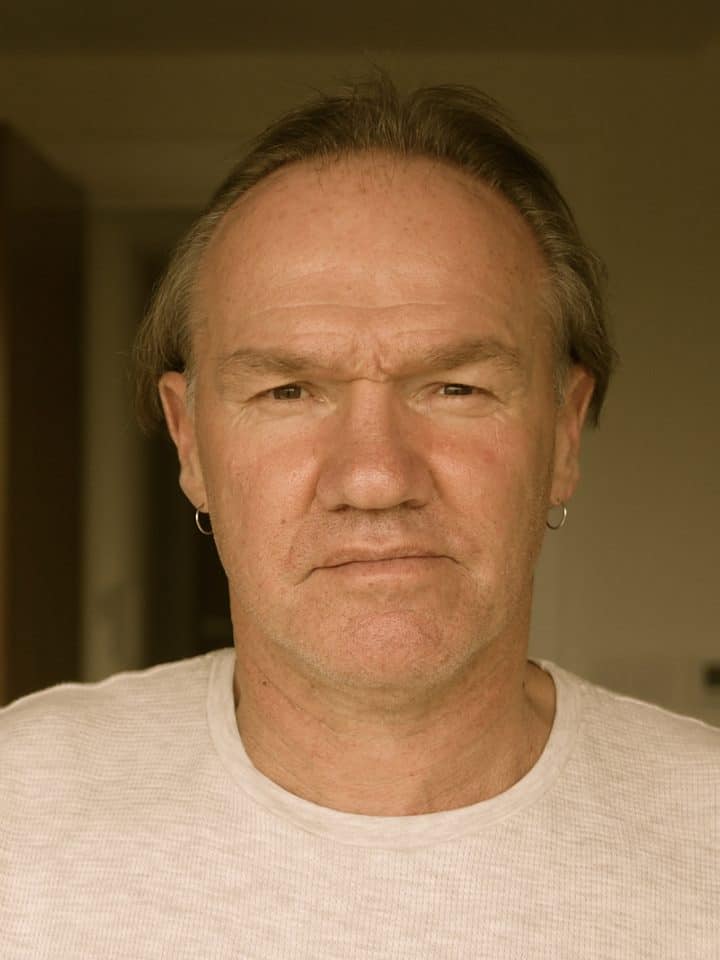

The Cook statue is genuinely ludicrous. Therefore, unintentionally or not, it accurately represents the history it celebrates, being the ridiculous but damaging mythology of terra nullius. Should Cookie be toppled? Or perhaps forced to remain on point and suffer his embarrassment? My close friend and past colleague at Victoria University in Melbourne, Professor Gary Foley, has suggested that rather than remove colonial monuments, he would lead an expedition to seminal sites of colonial memory and confront the lies of history they produce with an exercise in truth-telling. (He has suggested a national bus tour!)

In the last eighteen months I have spent a lot of time walking Country and reflecting on its ability to sustain my mental health. I have lived on Wurundjeri Country for most of my life and regularly walk or run the banks and walking tracks of the Birrarung (Yarra) River. I have previously written about the care that Country provided me following the sudden death of my younger brother, Wayne, in 2019, when, during a time of acute grief, I visited the river most days over several months and was emotionally strengthened by the experience.

More recently I have been regularly walking on Boonwurrung Country in Melbourne’s west, attracted to the Jawbone nature reserve, home to many species of birds, including migratory birds that fly to Boonwurrung Country each year from the Northern Hemisphere to nest and produce new life. The walks are sustaining. They also offer the opportunity to reflect on and defer to Country, which is an act of humility and cultural education. I am not certain if I will write about Jawbone in the future, but I know that if I do so it will be with a voice of respect.

The connection between my discussion of walking and the presence of colonial monuments on Aboriginal Country may appear obscure. In fact, I see a direct connection. The strength of Country is such that its authority cannot be displaced by littering landscapes with inanimate objects that represent a purposely fictional past disguised as the history of the nation.

I wonder if we need monuments at all. Country is living and dynamic. It holds the knowledge we require to enable us to come to terms with our duty to assist in protecting it against the ravages of climate change and ecological destruction. The stories of Country we need to hear, experience and learn from are infinite. They are held in the soil, in water – salt and fresh – in the night sky above. They are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories of deep time, and alongside them, statues to great men remain puny and petrified.

Cover Artwork by Tom Munro-Harrison follow on insta tom_munro_harrison